Although some people will only know We’re Going on a Bear Hunt as a picture book by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury, the text is adapted from an American folk song and many children of my generation will have known it as a scout and guide campfire song long before the picture book was published.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is one of the most celebrated examples of a picture book adapted from a song. Song lyrics often need some authorial tinkering to make them work well as a picture book text and the onomatopoeic sounds in the book (Swishy swashy! Splash splosh! etc.) and the verses about the forest and the snowstorm are both Rosen's invention.

When an editor asked me to adapt the song a few years ago, I decided that the first thing I needed to do was reduce the repetition. While a degree of repetition is often encouraged in picture book writing, I felt that having the same phrase repeated five times on every spread would become a little tedious, so I replaced two of the repeated phrases in each verse with a rhyming couplet.

So this first verse of the original folk song:

She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain,She'll be coming ‘round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!

Became this in my picture book version:

Song often make it onto the page without any authorial tinkering. There are plenty of picture book adaptations of Over in the Meadow and Old MacDonald had a Farm that feature the original lyrics …

… but there are also quite a few adaptations that have been re-written to include a more exotic, mechanical or flatulent cast of characters.

While all of the above examples are adapted from folk songs, picture book adaptations of contemporary songs have become increasingly common in recent years. One of the first examples I remember seeing is this 2007 adaptation of the Peter Paul and Mary song Puff the Magic Dragon illustrated by Eric Puybaret.

Since then, contemporary songs by Bob Marley, Dolly Parton, John Lennon, Kenny Loggins and many others have been adapted into picture books.

Illustrator Tim Hopgood has produced a series of picture book adaptations of classic 20th Century songs.

As picture books adapted from songs have become increasingly popular, the interval between the song coming out and the picture book being published seems to be reducing. Last year’s picture book adaptation of When I Grow Up, illustrated by Steve Anthony, was published just seven years after the song first appeared, in Tim Minchin’s Matilda the Musical.

And the picture book version of Pharrell Williams’ Happy! (illustrated with photographs) came out only one year after the song was released!

So if you’re a picture book author or illustrator looking for ideas, you might try flicking through an old songbook or switching on the radio. If you’re lucky, you might discover the inspiration for the next We’re Going on a Bear Hunt!

In the meantime, if you know of any good picture book adaptations of songs, do tell us about them in the comments section below.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.

Find out more about Jonathan and his books at his Scribble Street web site or his blog. You can also follow Jonathan on Facebook and Twitter @scribblestreet.

See all of Jonathan's posts for Picture Book Den.

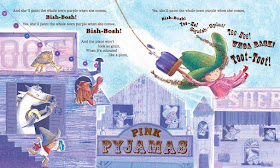

I also replaced most of the folk song's later verses – including the ones about sleeping with grandma and killing the old red rooster – with new verses. The new verse where the cowgirl paints the whole town purple was a cowboy-hat-tip to the Clint Eastwood western High Plains Drifter, in which an enigmatic cowboy literally paints a whole town red.She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!

Yes, she'll whistle like a train,

As she speeds across the plain,

She'll be coming round the mountain when she comes,TOOT-TOOT!

|

| One of Deborah Allright's spreads from She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain (now out of print). |

Song often make it onto the page without any authorial tinkering. There are plenty of picture book adaptations of Over in the Meadow and Old MacDonald had a Farm that feature the original lyrics …

Since then, contemporary songs by Bob Marley, Dolly Parton, John Lennon, Kenny Loggins and many others have been adapted into picture books.

And the picture book version of Pharrell Williams’ Happy! (illustrated with photographs) came out only one year after the song was released!

So if you’re a picture book author or illustrator looking for ideas, you might try flicking through an old songbook or switching on the radio. If you’re lucky, you might discover the inspiration for the next We’re Going on a Bear Hunt!

In the meantime, if you know of any good picture book adaptations of songs, do tell us about them in the comments section below.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.

Jonathan Emmett's latest book is Alphabet Street, a spectacular lift-the-flap alphabet book illustrated by Ingela P Arrhenius and published by Nosy Crow. Although it's NOT adapted from the Prince song of the same name, it is written in rhyme and has all the makings of a toe-tapping global smash hit if anyone is interested in buying the song rights.Find out more about Jonathan and his books at his Scribble Street web site or his blog. You can also follow Jonathan on Facebook and Twitter @scribblestreet.

See all of Jonathan's posts for Picture Book Den.