It always looks like picture books spring into being perfectly formed, so it's fascinating to see the journey of bringing a picture book into existence, and lately I've been lucky enough to sit in on the brilliant Just Imagine's An Audience with... featuring Sydney Smith. So today I want to show you a bit of the book he talked about, plus a bit of Jon Klassen's latest book The Skull, and wonder about who these books are really for.

Do You

Remember by Sydney Smith

|

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

|

We're in the dark, close up, with a boy and his mum in bed, and they start playing a game of Do You Remember.

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

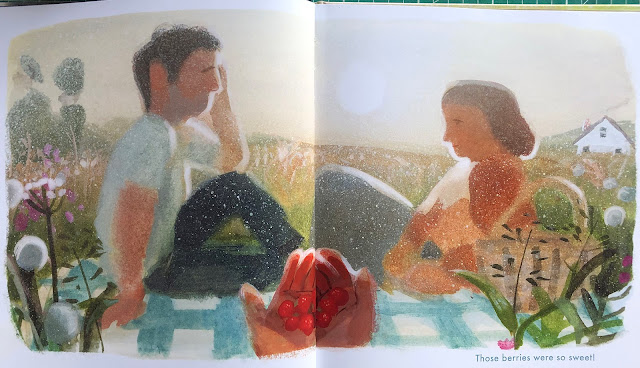

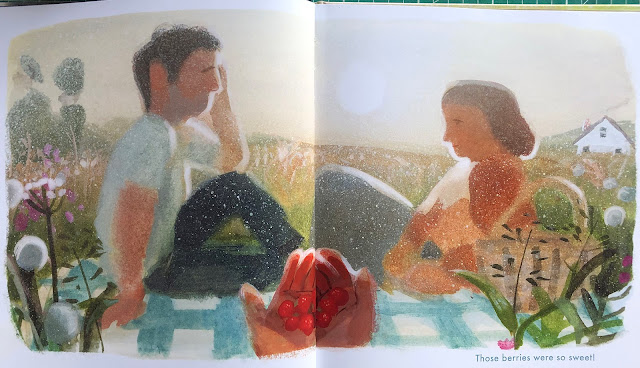

With the first memory we're in the summer countryside with a blue checked picnic rug.

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

The memories feel swiftly painted, and the first blob in the grass - that's our boy hunting for berries. The fragments have the feel of remembering, before the page turns and there's the whole picnic from the boy's point of view.

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

Below is one of Sydney Smith's sketches for that scene.

|

by Sydney Smith

|

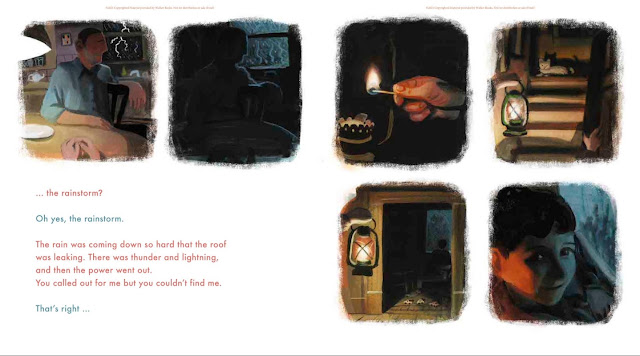

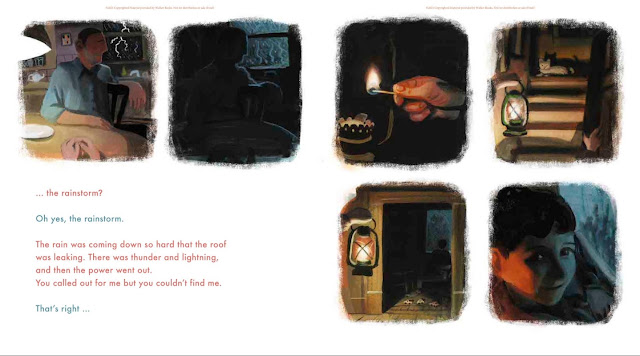

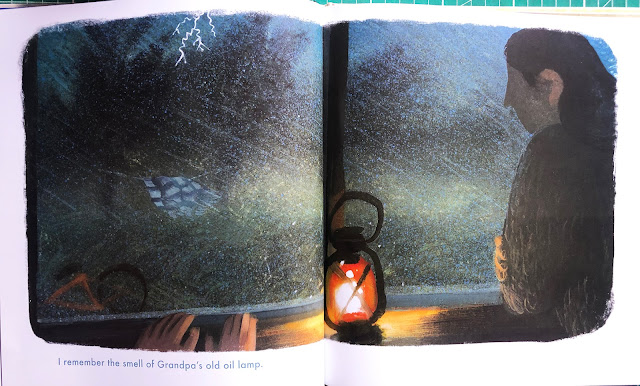

Here's the remembered night of the storm - but there's more disruption going on than just a storm...

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

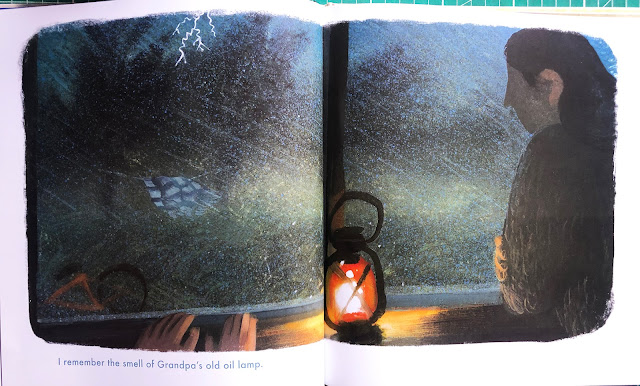

The

boy and his mum look out into the stormy garden and his new red bike

and the blue checked picnic blanket are being ravaged outside.

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

We can wonder about weather and light

reflecting inner turmoils and there's been some great thunderclap and their lives are going to change.

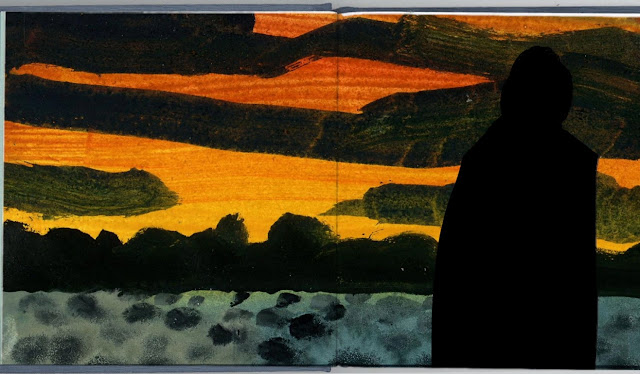

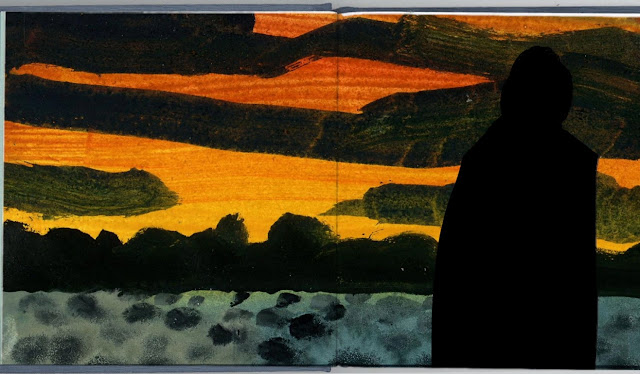

Here are some of the sketches Sydney showed at An Audience with - capturing a mood, a memory, in landscapes.

| |

| by Sydney Smith |

|

| by Sydney Smith |

|

| by Sydney Smith |

The boy and his mum leave for the city, leaving the dad behind. Here's a sketch of city driving - I love the zinging red light blobs.

|

| by Sydney Smith |

Here's the scene in the book:

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

The bear is a gift from the boy's dad, who they have left behind, to start again, just the two of them in the city. So where we started, the mum saying "Do you remember?" in the darkest time of the night, is maybe a night of not sleeping because of huge change and upheaval. Punctuated through the memories we see the boy and the mum in bed, as the first dawn light starts to fall on them, and the sun comes up on a new day. .

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

...and then we see what they've been watching emerge from the gloom through the night:

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

All the things they've brought with them from the country: that blue checked rug, the bike that is always slashes of the brightest red, the oil lamp from the storm: all the memories.

It was amazing seeing the quantity of paintings Sidney Smith made as he was discovering the book he was trying to make, inching towards a sort of crystallization of memory with landscape and mood to tell a story of family break up, but central to it is the boy and his mum, trying out being just the two of them together. The last image is them together, but it's framed as a memory would be, and it feels like the author is reaching in from the future to show this too will be what he remembers.

|

| From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith |

And now, to a Tyrolean Folktale retold.The Skull by Jon Klassen

Jon Klassen is the master

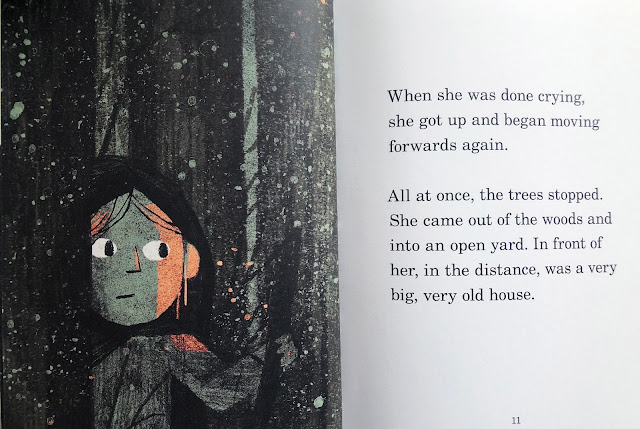

of the impassive face, the baleful eye. The Skull opens with Otilla running through the darkness. One night, in the middle of the night, when everyone else was asleep, Otilla finally ran away. We never know for sure what she's running away from, but that 'finally' seems to be important.

|

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

|

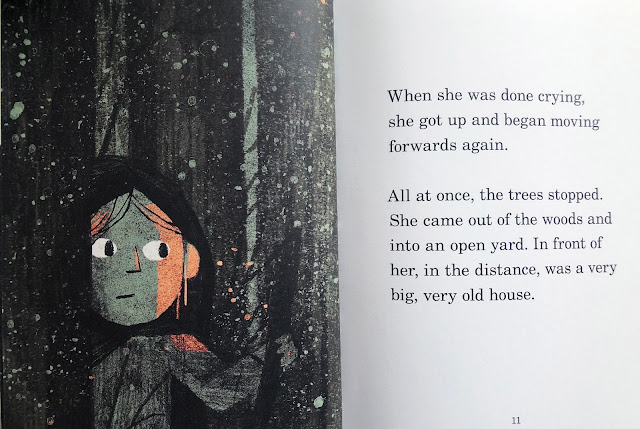

Here's Otilla after she's tripped and fallen and had a good cry. Now she has done crying, and a light of hope is falling on her face, from the sun rising behind a massive mansion she has come across. And living in that mansion is a disembodied skull.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

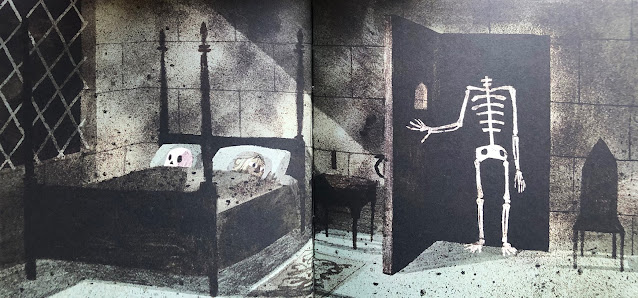

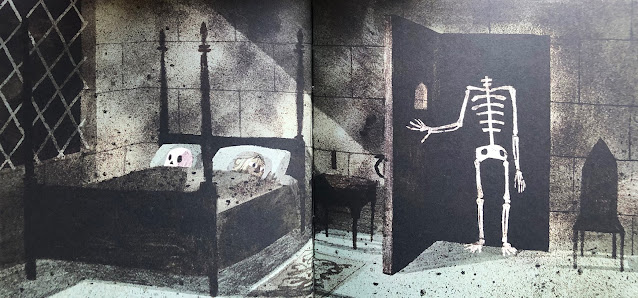

The skull is an interesting challenge: how to make an impassive skull into something we can care about. Suddenly coming across a skull - especially an alive one - would utterly fill me with terror. But this skull has no visible teeth or separate jaw, and what this does is take away the tendency skulls have to grin, this makes it into a quiet reflective sort of skull. The skull absolutely looks the same all the way through, but it is what the skull says that make it an endearing skull. Here below is the skull 'drinking' tea, and really enjoying the tea even though it has run through him out onto the chair. The blankness of the skull means all this hope and tea-enjoyment and vulnerability can be projected onto him.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

The skull needs Otilla, and it turns out he is visited nightly by a terrifying headless skeleton. Otilla

takes a terrible final vengeance on the skeleton, smashing it to pieces, burning it up, and then sinking the ashes in a bottomless well, in utter cathartic total destruction. Has this helped destroy what she's been running from too? Otilla’s resourcefulness,

tender tea-making and ruthless brutality towards headless skeletons is admirable. The story is thrillingly dark and scary, and also has a skull as an unlikely hero.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

But when you finish this book there are many

questions. Who was the headless skeleton? Was the skull once part of the skeleton? Why didn’t

the skull want to be reunited with the skeleton? What would have happened if the skull and skeleton got joined back together again? What was Otilla running away

from? Will she ever go home? And I love a book that leaves you with questions,

a story that is a bit unresolved. As you walk down to catch the bus you can have a really

good ponder about it, the story sticks around because your mind isn't finished with it, and it makes you want to talk about it to someone else.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

So, who are these books really for?

Both of these books are by

author/illustrators and the pictures are doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Do You Remember is like a work of autobiography, capturing the feelings of memory using light and colour to evoke a mood, a moment, with loose paintwork. It's not in full focus and that unresolvedness makes images feel momentary, but also there's room for our imaginations to come in and do some of the resolving. There's also space for us to wonder what happened and why the boy and his mum had to move and start anew.

The Skull takes us into a dark and scary place with Otilla. I loved going there, and I think it's a brilliant exploration of the scary and perfect for an audience of children and everyone else too. Words, in The Skull, do as much work as the pictures and are beautifully understated. Also, it turns out this book is a bit about memory too, because it started in a library in Alaska, where Jon found a story called 'The Skull'. The story haunted him afterwards and he kept thinking about it. Eventually he wrote to the libary in Alaska and he got to find the story and read it again. And then discovered that in the mean time, his mind had rewritten it for him into something completely different.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

Reading

pictures is something that people of all ages can do. I think picture books are special because there’s no other way of telling a

story that has the same powers. These books couldn’t say what they need to

say in any other format. The story of the pictures is deep and open-ended and

resonant and being conjured by our imaginations.

|

| From The Skull by Jon Klassen |

Our education system always ranks words higher than pictures; the words are serious, the pictures are decorations. If the pictures are serious, then it's Art and that belongs in a art lesson. Pictures: we can be looking into them with as much curiosity and insight as we would bring to literature.

My two barometer questions of my favourite picture books are: Is it for everybody, are all welcome? And: When you get to the end, do you feel like you've been taken somewhere utterly else? Been lost spellbound in the picture book's world? The book is a door into another world - to being transported, being taken into someone else's interior world, sharing what it feels like to be someone else.

Picture books have inclusivity - for everyone, but especially for children. Picture books allow older children instant access, to plunge straight in to the story even if they are not a fluent reader. Pictures are always open to your own interpretation, there's no right answer, so pictures are a very good thing to discuss - so readers can be expert Picture Book Detectives, readers of pictures.

The Skull and Do You Remember both have a sort of openness at the heart. We never know what Otilla is running from or how the bodiless skull came to be. The events that lead to the boy and his mum starting a new life in Do You Remember are also not spelled out, they are available for us to wonder about. The central issues that brought the characters to where they find themselves are a bit of a mystery, and open for us to ponder.

|

A strange surreal image from Paradise Sands, by Levi Pinfold

|

So who's it for? Maybe that's the wrong question, Maybe the reason why something is a picture book, is that a picture book was what the maker needed to make in order to tell the story they wanted to tell. So the question was "How can I tell my story?" and a picture book was the answer.

Picture books are a special unique format for telling a story where ALL are WELCOME - but if the books have to sit on a shelf marked 'for children' everyone else thinks they're not for them.

Last week Julia Donaldson was on Radio 4 - with the excellent help of Frank Cottrell Boyce - lamenting the poor coverage children's books get in the press and on radio. What are thought of as Children's Books get put on a far dusty shelf and people who like reading what are thought of as Children's Books feel vaguely embarrassed.

Maybe that's because of the label, and if we could see picture books especially as not exclusively for children they could get a bit more notice.