In April, Lynne Garner wrote a blog post for Picture Book

Den called ‘Having Fun Making Stuff Up’.

She spoke about attending a writing retreat with the Scattered Authors

Society. During the retreat, Lynne took

part in a workshop where she was encouraged to use drawing as a way to generate ideas for picture books. http://picturebookden.blogspot.co.uk/2018/04/having-fun-making-stuff-up-lynne-garner.html

As many authors and illustrators know, one of the most

popular questions we get asked is….‘Where

do you get your ideas from?’ and it can be quite a tricky question to

answer because the truth is ideas really are everywhere! And yet, I still find

it interesting to hear what people say. Their

answers often make me realise how a method that works for one author or illustrator

might not be the best approach for another.

But it also shows there is no right or wrong way to find ideas.

At the London Book Fair this year, I was excited to attend a

talk from our Children’s Laureate, Lauren Child. As part of her laureateship, Lauren wants to

encourage people to ‘let children dawdle and dream’. She wants to set up a challenge on her

website for people to ‘Look Down’

and notice, as they walk around, the small, forgotten or misplaced items on the

floor and to consider what the story around these objects could be. It reminded me of another post by Lynne

Garner where she challenged Picture Book Den readers to make up a story based

on some of the objects she’d photographed on a walk. http://picturebookden.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/Lynne%20Garner?updated-max=2017-10-23T07:00:00%2B01:00&max-results=20&start=3&by-date=false

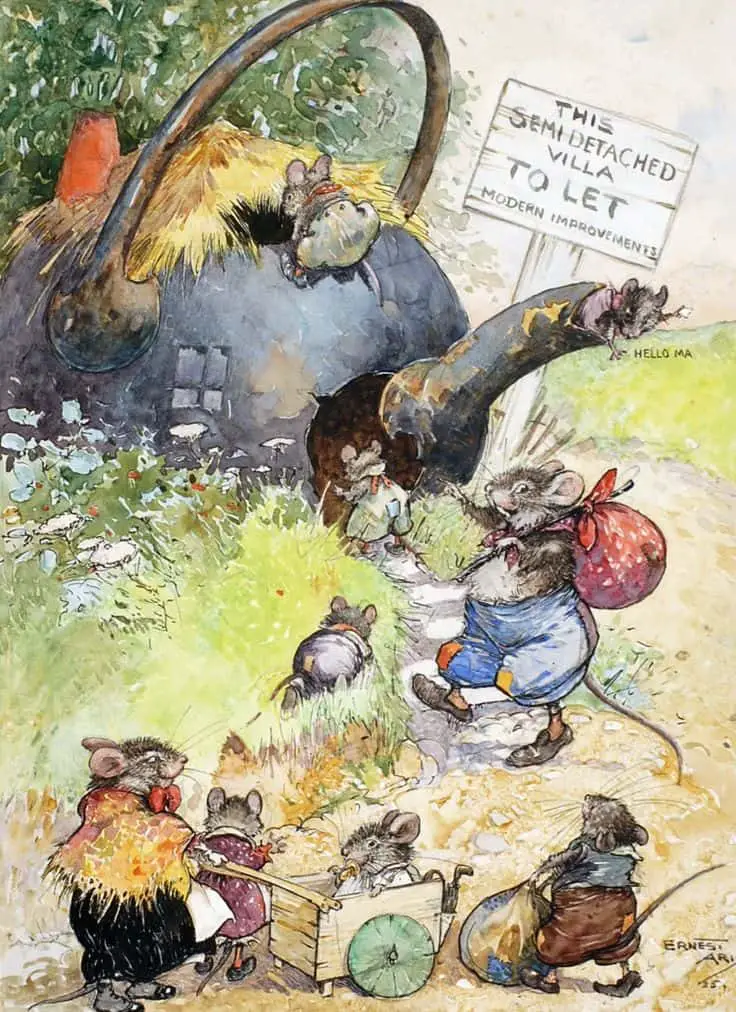

I once heard author, Tracey Corderoy, speaking at a Nosy

Crow ‘Picture Book Master Class’. For Tracey, looking through illustrators’

work and finding interesting characters can spark her to wonder ‘what could

this character’s story be?’ Picture

book author, Lou Carter, also told me that she often writes a story around a character.

The character is very much the starting point for her. I found this really interesting as it’s

something I rarely do. Perhaps it’s

because I’m not such a visual person?

Maybe this is also why I don’t use drawing to come up with new ideas?

I once heard author, Tracey Corderoy, speaking at a Nosy

Crow ‘Picture Book Master Class’. For Tracey, looking through illustrators’

work and finding interesting characters can spark her to wonder ‘what could

this character’s story be?’ Picture

book author, Lou Carter, also told me that she often writes a story around a character.

The character is very much the starting point for her. I found this really interesting as it’s

something I rarely do. Perhaps it’s

because I’m not such a visual person?

Maybe this is also why I don’t use drawing to come up with new ideas?

I often get my ideas

because I like to play with words. My first book ‘Gecko’s Echo’ (with

illustrator Natasha Rimmington) came about simply because I liked the sound of

these words together. Next year, I have

a second book coming out with Ben Mantle- I can’t reveal what it is called just

yet but it also has a rhyming title that very much inspired the story and,

again, this came about from playing with language. Mine and Kate Hindley’s latest book, ‘The

Knight who said No’ was initially about a viking (rather than a knight) and this

idea came to me when I was playing around with the words ‘The vikings are striking!’

I’ve always loved rhyme

and rhythm. Sometimes I find rhythms

that I particularly enjoy and I see if I can write a story around that

rhythm. For example, I love the rhythm

in ‘Bad Sir Brian Botany’ by A.A.Milne:

He walked into the

village in his second pair of boots.

He had gone a hundred

paces, when the street was full of faces,

And the villagers

were round him with ironical salutes.’

I mean…What a fantastic rhythm!!

I was in Australia when I re-read this poem and that evening

I was looking at the fruit bats in the trees. I then asked myself that very important

question that we often ask ourselves as authors and illustrators…WHAT IF? ‘What if there was a fruit bat who didn’t like

fruit?...what would happen then?’

And I wrote around the Sir Brian rhythm as a challenge to

see if I could do it.

‘Once there was a

fruit bat and the fruit bat’s name was Jeremy.

Jeremy had always

felt he didn’t quite belong.

No he wasn’t like the

others and his sisters and his brothers

Used to look at him

and giggle ‘cause he always got it wrong.

And worst of all were

mealtimes. Jeremy just dreaded them.

His brothers and his

sisters used to think it was a hoot!

See it isn’t very

easy when your dinner makes you queasy

And Jeremy refused to

try a single bite of fruit.’

I use the ‘what if’ question a lot during my school

visits. What if it really did rain cats

and dogs? What if you woke up and your teachers had turned into zombies? What

if children ruled the world? (Cue loud cheers from the class!) The children are generally fairly excitable by

this point but I then encourage them to come up with their own ‘what if?’ ideas

and their suggestions are truly brilliant! In fact, I might have to steal some of their ideas myself!

Further investigation into where people find inspiration taught

me that Abie Longstaff sometimes uses the childhood

games she played with her younger sisters as ideas for stories. Juliet

Clare Bell uses the artwork hanging

on her walls. Penny Dolan once wrote a guest blog for Picture Book Den and put

it brilliantly…’Picture books are a pleasure to write once you’ve got an

idea.’ One of the places she gets

inspiration is from the schools themselves when she is doing school visits. http://picturebookden.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=penny+dolan

Ideas really do come from many different places and you

might find that you have certain tendencies or preferences when hunting for your

own? So….Where do you get your ideas from?