Pippa Goodhart: I'm delighted to welcome to very original thinking picture book creators to the Picture Book Den. Stefanie and Miriam's 'I Am A book. I am A Portal To The Universe' won The Royal Society's Young People's Book Prize. So I've asked these creators to explain how that book came about ...

I’m Stefanie Posavec, a designer and artist who works with data. Often I co-create data artworks with my longtime collaborator Miriam Quick, a data journalist.

Within our shared practice, we explore unusual ways of communicating data, particularly those that are playful, multi sensory, and accessible to all ages, like creating a set of data necklaces you can touch and wear to learn more about air pollution (Air Transformed), or creating playful experiences to collect data from visitors in order to turn it into an artwork (National Maritime Museum).

One of our latest projects is I am a book. I am a portal to the universe., published in 2020 by Particular Books (Penguin Random House). I come from a publishing background, both as a book designer and as an author (Dear Data and Observe, Collect, Draw!), but this was my and Miriam’s first book together.

We came up with the book’s idea while brainstorming new ideas for collaboration in the summer of 2018. We knew we wanted to make a book using data, but were feeling weary of the standard data-driven, infographic book format, so we challenged ourselves to explore a different approach.

After some brainstorming, we came up with our big book idea, asking ourselves: “What if we made a book where the book itself is the measuring device?”

We began to develop the general concept and brief:

● The book itself is a measuring device, where all the measurements are embodied in the dimensions of the book itself.

● It’s a book for (almost) everyone, from children aged 8 and up to adults. Our goal was to write for the data-uninitiated or data-intimidated, people who wouldn’t normally pick up a book with ‘data’ or ‘science’ in the title. We wanted the book to be accessible enough for children, but entertaining enough for adults, with a bit of ‘bite’ and humour to it.

● No traditional charts or infographics were allowed in the book! We had an absolute ban on all of the trappings of a traditional info-book.

● Finally, our golden rule, and biggest constraint: all the data should be represented on a 1:1 scale, printed on the page at actual size.

That’s a complex brief, so how did we make it happen?

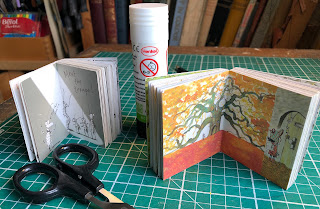

Once we secured a book deal, in order to develop the book we fixed its specifications – its dimensions, paper, number of pages and more – with Penguin Random House very early on, and they made blank dummy books to these specifications that we could then work with while we developed the content.

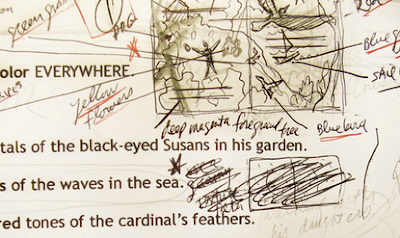

With our dummies in hand we started by brainstorming all the ways of communicating data using its form,

carefully measuring and inspecting every component and interacting with it, bending the pages, wearing it as a hat while chatting to each other virtually … and we started to find the beginnings of ideas.

As every data fact needed to be represented on a 1:1 scale, we looked for interesting measurements around the same size as the book, so lengths between .1mm (the human-egg-sized dot on the end of the arrow on the left hand page below) and 20cm (the height and width of the book, and the diameter of the grey circle on the right, which represents one giant single-celled organism).

And we also explored how the reader’s interactions with the book could also communicate data: for example, in this spread the book invites you to hold it up to the sky, then tells you there are six sextillion stars behind the footprint of its two pages, when held at arms’ length.

Or in another spread you might be asked to slam the book shut as hard as you can to hear how noisy sunshine would actually sound (if space wasn’t a vacuum)… this is not an e-book (and never will be)!

As for the narrative, we developed a more fleshed-out concept and narrative vision. We realised the book should speak directly to the reader in the first person and have a strong personality.

For example, on this spread, the book (rather pompously) declares itself to be ‘a portal to the universe’. It’s a universe that’s dynamic, constantly moving and changing, full of countless mysterious, elusive things flying through us or away from us.

Our goal was to make scientific ideas from this dynamic, mysterious universe accessible and approachable for readers of all ages. We tried to include concepts that weren’t common knowledge, but that anyone could grasp, with a few mind bending facts thrown in for good measure.

An example can be seen in this spread, which is about the bizarre consequences of relativity. The book tells you that, if you stood it upright on a table, time would pass a tiny fraction of a second slower at the bottom of the page than the top because it is closer to the earth’s centre of gravity.

We also made sure that all of the book’s information was fully referenced by adding a section we called ‘the small print’ – a big appendix at the back of the book that explains all the background, calculations and assumptions behind each spread.

So after 2.5 years of hard work, did we actually succeed in making a book that went beyond the typical infographic book? We hope so because just recently, we won The Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize 2021, a prize that rewards excellent, accessible STEM books written for under-14s.

Best of all, while the shortlist was named by a panel of adult experts, the final decision was based on the voting of 11,500 young people aged 8-14, and this is why winning this book prize means more to us than any other award we’ve won.

The young people’s decision to vote us the winner is testament to the fact that people respond to these new not-your-standard-infographic-book approaches that we were working with, and that there is value in pushing past standard publishing formats and trying something new.

What’s next for our shared publishing career? We are currently working on another project together that we hope will build on the success of our first book and also appeal to an all-ages audience, watch this space (and keep your fingers crossed for us)!