I’ve started teaching a course on picture books and as I

break down the basics to other writers, I realised that I’m articulating my own

understanding. My writing, especially in the medium of picture books, comes

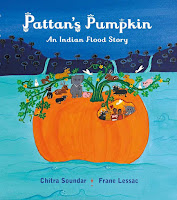

from my lifelong love of picture books, from this moment, I was handed this

book when I was 7.

I read picture books and comics as much as I can, growing

up, and when I started writing way back in 2003. I still read way too many

picture books and often most ideas present themselves to me in 12 spreads.

Along with this love for picture books, I’m also a

storyteller. I think I told stories even when I was four and the love for oral

storytelling never really left me even when I was working in the corporate

world.

Here is my process of how I search, find and finesse a folktale for a modern

audience.

Finding a story:

I usually choose a story from my own culture or a trickster tale. I read quite

a few stories from collections I’ve accumulated over the years to identify

which story connects with me. I need to get the “theme” of the story and I want

to be able to see the story in scenes, rather than a quick joke.

If I do choose a story that is not from a culture I’m

familiar with, I would check if there are enough independent “first-hand”

sources I can rely on for accuracy of representation. I’d want to know if this

story has been retold or adapted or written about by people who are native to

that culture and what do they think of it. Often folktales have hidden allegory

and meaning that will work at a different level than the “story” itself and I

might inadvertently cause hurt or offence to people by re-telling this story.

My search takes me into libraries, Internet archives of

ancient texts and research notes because modern retellings or “collections”

might be derivative and I would try and find as many “native” sources I can.

Evaluating for a Modern Audience: There are many funny

stories in Aesop fables or Panchatantra or our epics that might not be suitable

for today’s children. Many of these stories are true to their time and

geography. So a story about “girls knowing their place” or “a cruel stepmother” or "old women are witches" are not only inappropriate but also harmful for today’s child.

So I read and understand the underlying concepts of each of

these folktales and think about whether the protagonist and the events of the

story are telling a tale suitable for today and beyond. While we can’t go back

and erase our past, or justify some of the notions, the least we could do is

not to propagate unhelpful stereotypes – whether it’s about gender, age, sexual

orientation or cultures.

Adapting the Story: Now comes the techniques of writing a

picture book. I need to know enough about the story to be able to adapt it. As

I said before, I would try and find as many variants of the story I can. I’ll

try and find archives with original text or translations.

Having absorbed the story, these are my techniques to adapt

the story:

a)

Understanding its spine – what’s the story

really about? What’s the message and essence of the story? In this, oral

storytelling and adapting have the same goal. I normally break down a story

into 10 simple scenes or sentences. Or 5 things I need to remember and then

distill it into “a message”. Once I know this, I can then adapt the story and

still be able to keep the essence.

b)

Who are the characters? Especially when I’m

working with trickster tales, the characters in the story are crucial for the

logic of the story to work. Like Stork and the Fox in Aesop Fables, or the

Crocodile and the Monkey in Panchatantra. The characteristics and the

“character” – who is evil, who is tricking whom, who is symbolised as clever –

all of that will need to be worked out. Often keeping the same characters as

per the original story is sufficient. Sometimes I’d want to change it. When

changing the characters, I’ve to make sure that the “symbolic” nature of their

characters will still work.

It’s important to know the cultural

archetypes here. In some cultures some animals and birds are clever / evil /

cunning and if I need to credit the culture, then using an alternate one or the

wrong one will take away the authenticity.

c)

What’s the punch line and how do I get there? I’ll

need to understand what are the relevant scenes that need to have happened for

the punch line to work. But at the same time, we need 12 scenes in the picture

book that are different from each other.

Here’s where research pays off – knowing

the geography of the story, knowing the other characters will help.

Also as a storyteller, the embellishing

happens here – adding more scenes to show the allegory or the true nature of

the characters will help a child reader understand the punch line better.

d)

Word count and other practical considerations:

Most modern picture books are under 400 words with exceptions of course. I need

to be able to tell the 12 scenes with enough happening between the scenes and

still keeping the word count down.

The other thing I’ll think about

is viewpoint – which character is telling the story? Am I going to use the

voice of a storyteller? Is my language going to be modern or folktale-ish? Is

this story going to be billed as a re-telling or an adaptation?

e)

Adapting vs Retelling – Whether it’s the

Gruffalo or the True story of the Three Little Pigs, or my own A Jar of Picklesand a Pinch of Justice or Pattan’s Pumpkin – the story can be hidden under a

completely new setting, cast of characters and a modern retelling.

Whether or not the reader knows the underlying story, it will still be fun for them. Of course, in all of my adaptations, I’ve made it clear that I’ve adapted traditional tales. Sometimes a story is in folk-legend widely that you might not need to mention it.

For those who are starting out to write picture books and

grappling with “where do I get ideas?”, adapting folktales can be a wonderful

exercise in research, structure and plotting. Folk tales have plots that have

worked for hundreds of years and can be useful in showing us how to construct a

regaling tale.

If you enjoyed reading this post, do share your

favourite folktale adaptations

Chitra Soundar is the author of many picture books and

retellings. Her latest book is an original story of two polar bear cubs

discovering the world. Find out more about You’re Snug with Me, illustrated by

Poonam Mistry and published by Lantana Publishing here.

No comments:

Post a Comment