Louis Franzini PhD, in his book Kids Who Laugh, identifies 13 categories of humour which children recognise – I calculated once that 10 of them are already being used in books meant for pre-schoolers and infants. Which has to point to the fact that humour is very important to humans. This conclusion is certainly borne out by numerous studies Franzini cites into how having a sense of humour is linked to higher levels of intelligence, creativity and flexible thought processes, and is also associated with higher self-esteem, good self-control and a sense of empathy.

Other research (despite a new study showing that virtually everything about us is governed by nature not nurture) shows there is good evidence that a sense of humour is acquired as a child, so it’s jolly lucky it sells both picture books and poetry!

So – I can hear you wondering what those 10 types of humour are, and frantically totting up types on your fingers. Verbal wordplay such as I have just used is one… alliteration fills this job nicely. Children’s poetry and the poetic language in many children’s picture books employ this simple way to make the text fun to say, fun to listen to, and to help with the humour of what the words are saying. Language in everyday life is logical, orderly, and usually unrhythmic, without sentences ending in rhyming couplets, so it is made funnier to children when they do. Lynley Dodd’s picture books are wonderful examples of both alliteration and rhyme – here’s a page of Schnitzel von Krumm’s Basketwork:

Surprise is number two in my list. Laughter is an automatic reaction to the release of tension. In Colin McNaughton’s ‘Boo’, Preston the Masked Avenger piglet goes round town shouting ‘boo’ unexpectedly and gets his come-uppance when he does it to his dad pig, and dad pig sends him to his room and does it back.

Number three is slapstick. Number four is absurdity. ‘Funnybones’ by Janet and Allan Ahlberg was a book that never failed to have my 4 year old son helpless with laughter. The book is also full of alliteration. A big skeleton, a little skeleton and a dog skeleton who live down a ‘dark, dark cellar, down a dark, dark staircase’ etc. go out at night to scare people, but mainly end up scaring themselves. The big skeleton throws a stick for the dog skeleton. The dog skeleton jumps for it and bumps into a tree, and ends up as a little pile of bones. The big skeleton and the little skeleton try to put him back together again, but get his skeleton all mixed up. The dog can only say ‘WOFO’. They try again, and this time he says ‘OOFW’. Then ‘OWOF’ and ‘FOOW’.

My son could not read, so it fascinated me that the idea that the dog’s ‘WOOF’ was the wrong way round struck him as so funny. Clearly the word sounds are being listened to along with the meaning by this age This must help with the acquisition of reading skills. Alliteration, wordplay, slapstick, absurdity and the realization that letters in the wrong order say something different, all in one book. No wonder it is still on sale – my son is 26!

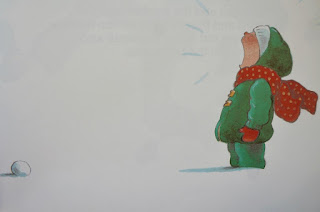

Human predicament is my number five. Obviously the predicaments available to picture book authors are narrowed to those that are pertinent to the very young, and a book we bought in Canada, I Have To Go!, by Robert Munsch, illustrated by Michael Martchenko shows this one perfectly. Andrew is asked by his parents if he needs to go pee before setting off on a journey; “No, no, no, no,” said Andrew. “I have decided never to go pee again.” Obviously five minutes into the journey he has to go, very urgently. Later he goes to play in the snow at Grandma’s without having a pee first, and his snowsuit has 5 zippers, 10 buckles and 17 snaps.

Everyone has to pee. The child being read to knows this. The humour for the child is in the knowledge and having this knowledge, and knowing what is going to happen fosters empathy (feeling for the child) at the same time as self-esteem (knowing he knows better) and the ability to foresee the logical conclusion to a train of events.

Six, defiance, and seven, incongruity are ably illustrated by David McKee, in his book Who’s a Clever Baby Then? “Who’s a clever baby then?” said Grandma. '“And where’s my oofum boofum pussy cat? Say ‘cat’, Baby.” “Dog,” said Baby.’ Saying ‘No’ and getting away with it, being naughty, getting one over on a parent, brother, sister or friend, is extremely appealing to a young child who has little control over their own life. The incongruity of the baby saying dog instead of cat is also funny to the child listening.

Two monsters by David McKee uses mainly violence, type number eight. The two monsters argue over whether day is disappearing or night is arriving – as they live on either side of a mountain they cannot see what the other monster can.

They end up trading very funny insults and then throwing rocks at each other until the mountain is destroyed and the truth that they are both right is revealed. Their argument is resolved – hopefully revealing that arguments are often absurd and a happy resolution is possible. Incidentally I am convinced David McKee has listed types himself as I found loads of his books each of which mainly used one category of humour.

Exaggeration is number nine and of course ten thousand times more important than any of the other categories. It is often paired with absurdity. Carl Norac’s ‘My Daddy is a Giant’, illustrated by Ingrid Godon, is a gorgeous example of exaggeration.

The exaggerations are affectionate, funny and descriptive. ‘When the clouds are tired, they come and sleep on my daddy’s shoulders’.

Simple puns is the final category. These are not usually used until the child is older, but can be used when the text is helped by pictures which helps the joke easy to understand. TWO CAN TOUCAN by David McKee uses a pun. It’s about a plain black bird without a name. He goes to seek his fortune. Because of his big beak, he’s useless at most jobs -except carrying two cans of paint.

All these picture books are fairly old as they are the ones we had when my children were small. But any I’ve bought or read since have all employed a mixture of the above types of humour. I’m a poet, not a picture book writer (yet!), but of course all these tools and types of humour are used in poetry too, for ages 3 up to 7 – and how remarkable is that?

Liz Brownlee, National Poetry Day Ambassador,

Liz's personal blog: http://www.lizbrownleepoet.com

Liz's blog for all things poetry related: http://www.poetryroundabout.com

Apes to Zebras, an A-Z of Shape Poems, Reaching the Stars, Poems about Extraordinary Women and Girls, The Same Inside, Poems about Empathy and Friendship.

Reference: Dr Louis Franzini, PhD. Professor of Clinical Psychology San Diego University Ca. Kids Who Laugh, New York, Square One Publishers, 2002

8 comments:

A wonderful post, Liz. I find that so often, when children are choosing books themselves, the ones they return to again and again are those that make them laugh! As you say, it's so very important.

Thanks for your fascinating post, Liz, until I read it, I'd never really thought about the different kinds of humour in picture books.

This is fantastic. Thanks.

Thanks, everyone! Humour has always fascinated me, and the fact that we all laugh at different things.

Terrific post! Thank you.

I laughed aloud (OK, snorted!) at the dog's 'woof', or rather 'owof', etc. Wonderful!

Violent, slapstick humour is the one I've never understood - as a child I hated Tom and Jerry and wanted Jerry to suffer, not Tom. Same with Sylvester and Tweety Pie, that bird deserved to be munched. Or maybe I just like cats...

Great post! Thank you

Super post, very interesting, thank you.

Post a Comment