A favourite might be our newest book because that’s still our baby. Or it could be the one we feel is the best quality, whatever that means. Or maybe it’s the book that has made us the most money. Or there could be a secret, emotional attachment to a book that only we know about.

So to start the New Year, six of us at the Picture Book Den thought we’d try and answer this tricky question. We’ve only allowed ourselves one book each, argh! Here are the personal favourite picture books of Jane Clarke, Jonathan Emmett, Pippa Goodhart, Paeony Lewis, Garry Parsons, and Lucy Rowland.

Jane Clarke

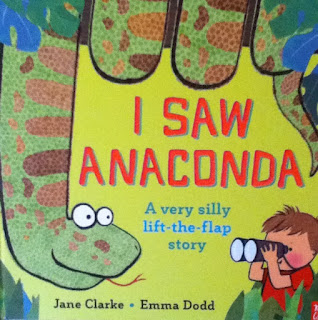

My personal favourite has to be I Saw Anaconda, illustrated by Emma Dodd (Nosy Crow, 2016)

The rhyme popped into my head on a once-in-a-lifetime adventure tour in Venezuela in 2008, and will always remind me of it. One of my sons was working there as a tour guide, and he took me and his brother to find anaconda. The rhyme took 9 years (and many rejections) before a publisher (Nosy Crow) worked out what to do with it. It was wonderful to be able to dedicate it to both my sons who now have families of their own. I saw anaconda has fab illustrations and clever flaps that include a pull-out snake. My four young granddaughters (including two who are part-Venezuelan) have already chewed/ torn/ generally loved to death several copies :-)

Jonathan Emmett

My favourite self-penned picture book is The Santa Trap,

illustrated by Poly Bernatene (Macmillan, 2009). It tells the story of Bradley Bartleby,

an obscenely rich, villainous child who sets out to trap Santa Claus so

that he can steal all of Santa's presents. One of the reasons I'm

particularly fond of the book is that it's slightly

autobiographical; as a child I used to build Santa traps. However,

unlike Bradley, I didn't want to capture Santa and steal his presents – I

just wanted to get a glimpse of him. So the traps I built were designed

to wake me up the moment Santa set foot in my room.

Pippa Goodhart

I've got a new favourite book of mine, and its Chapatti Moon (Tamarind, 2017). Why? Well, I love the pictures that Lizzie Findlay has done of Mrs Kapoor and the animals as they chase the chapatti that's rolled away. I love the clever design that includes a twist of the book to make you look up when the chapatti goes up into the sky. But I'm also proud of my text that ends as she saw ...' her chapatti moon slip-sliding down the sky. She held out her hands, and she caught it. "I shall eat the moon!" said Mrs Kapoor. It was just enough. She wanted not more. And it did taste wonderfully moony.' Next time you eat a chapatti, consider that thought. I suspect you'll also find that it tastes 'moony'!

Paeony Lewis

In monetary terms, there’s no way my favourite book could be No More Yawning (Chicken House/Scholastic, 2008). Instead it’s an old favourite for making me smile the most. It’s about a little girl, Florence, and her toy monkey, Arnold, and their bedtime antics.

We British are often reticent about blowing our own horn, but I do like the feisty ‘first person’ voice of Florence and the way the story builds. Plus now that I know more about art I appreciate further the fluid watercolour illustrations by Brita Granstrom. And I like the end papers and the spot varnish on the cover (little things make me happy!).

I particularly enjoy reading No More Yawning in schools because when Florence yawns, the young children join in too. Unfortunately, it’s embarrassing when outside the classroom I overhear children laughing and saying they yawned a lot in storytime – I feel compelled to explain to others the yawning WASN'T because the story was boring (really!).

I also like that the story encourages children to make up their own stories before they go to sleep. However, all this isn’t quite enough to make No More Yawning my favourite. What helps most is that my daughter was the inspiration for the story and it brings back memories, even if many years ago those bedtimes were frequently frustrating!

I think that’s enough reasons. Though it has to be the hardback version with the lovely endpapers.

Garry Parsons

When school children ask which of my books is my favourite I

almost always say it’s my latest publication but then inevitably I revert back

to Krong! (The Bodley Head, 2005).

In the story, Carl is playing in his garden when a spaceship lands and out steps an alien and his alien dog. Carl tries a succession of languages to try to communicate with the Alien who only speaks 'Noobanese'. Eventually the puzzle is solved but there’s also an identity twist.

In the story, Carl is playing in his garden when a spaceship lands and out steps an alien and his alien dog. Carl tries a succession of languages to try to communicate with the Alien who only speaks 'Noobanese'. Eventually the puzzle is solved but there’s also an identity twist.

What I like about this book is that it almost certainly requires

you to look back through the illustrations to spot the clues you would have

missed on the first reading. Looking back and studying the illustrations was

something I enjoyed as a boy, particularly in a book called What-a-Mess by Frank

Muir and illustrated by Joseph Wright, where you can spot an entirely separate narrative

going on alongside the main story. I also love that so much of the detail in Krong!

is based on things that were pertinent or existed in my life at the time,

including the two dogs, quite a lot of the furniture and that I was having

lessons in Japanese.

Lucy Rowland

'Meanwhile at the library, what a barbarian!

Wolf had tied up Mrs Jones, the librarian!'

Little Red Reading Hood publishes with Macmillan on 25th January 2018 (Eeeek! Not long to go!) and I really hope that people enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed dreaming it up.

______

So those are our six favourites. Have any choices surprised you? Some books are old, some are new, and they're not necessarily our top sellers, but we love them for our own reasons.