In the early 1980s, the world

was gripped by the threat of nuclear war. Soviet leaders were convinced that the US and its allies were a finger touch away from a pre-emptive strike and as

a schoolboy living in Berkshire it felt like we were right in the middle of

it.

I remember seeing foreboding images of giant mushroom clouds on posters and

T shirts and reading books on

building fall-out shelters.

I also remember watching a film, which might have been “The Day After” (whatever it was I wasn’t meant to be watching it), depicting a full-scale nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union, and it was terrifying! My friends and I would role-play what we would do the day after a nuclear

attack, build shelters in the woods and store supplies of cheese sandwiches and crisps. And with cruise missiles being

delivered to the nearby Greenham Common airbase it only fuelled our imaginations.

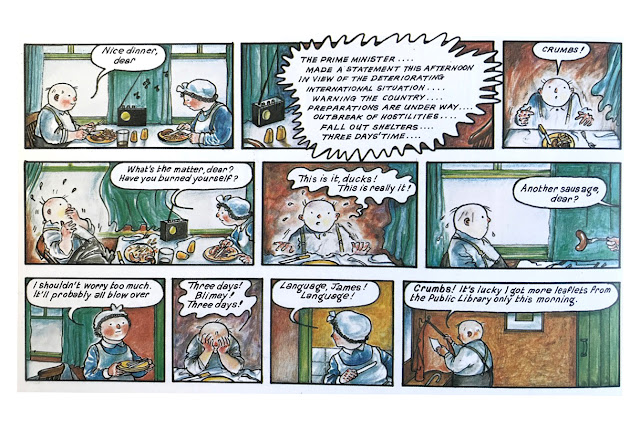

To add to the nuclear smorgasbord I read “When the Wind Blows” by Raymond Briggs.

The recent quarrels

between the United States and North Korea brought back my memories of the nuclear '80s and prompted me to re-read Briggs' graphic novel. Isn’t it funny how things come around!

“When the Wind Blows” follows

pensioners James and Hilda Bloggs, as they naively prepare for a nuclear attack under

the guidance of “The Householder’s Guide to Survival” which James has found that morning in the local library. The strike is predicted over the radio to arrive “in three days time”.

The tension and apprehension of

the ensuing attack increases over each page as the couple fumble to construct their makeshift

shelter out of doors and cushions.

Panel by panel the couple are edged closer

and closer to the moment of impact…

Until…

While it’s tempting to write

“BOOM” it is not necessary. The emptiness is all this spread needs and I

found it as astonishing and as powerful as I remember I did on my first

reading as a schoolboy. And it is this spread that has prompted me to write this post.

But what is it that makes this

page turn so arresting? After all, it is

a spread with no words and virtually nothing on it at all - just a pale pink edge

to an empty white .

But that’s just it. The eerie

silence after all the busy chatter is shocking and the simplicity of the white

is exactly how those film clips I saw as a boy described what the nuclear flash would look like when it hit, and within the story the timing is perfect. This empty nothing has so

much impact.

With the visual power of Briggs' wordless double spread in mind I hunted through my picture book collection for

other wordless double spreads to enjoy. Here are a few of my favorites, some

familiar and some less so, some light-hearted, some contemplative and a couple biographical.

The first is the forest made of rubbish from “The Tin Forest” by Helen Ward and illustrated by Wayne Andersen. (Templar 2001) Here are two spreads from the story. The first shows the reality of the old man's garden

...and then its transformation later in the book, into his dream paradise.

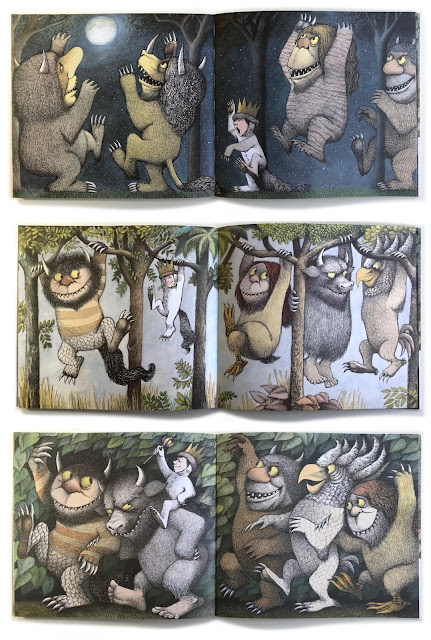

The inimitable “Where the Wild Things Are” by Maurice Sendak. (Harper & Row 1963)

Three wordless double spreads in a row of the “wild rumpus”. Not only giving the reader the raucousness of Max and his subjects messing about but also a sense of time passing and that they play until they can’t play anymore.

Another dream image, this one the imagined journey mapped out by a young Christopher Columbus in “Follow the Dream” by Peter Sis. (Knopf 1991)

A cruel blizzard sets in on Elephant island. From “Shackleton’s Journey” by William Grill. (Flying Eye Books 2014)

In the entrance to the upturned barn she has converted into an ark is Norah, calling to the animals as the rain begins to start.

And later them all waking up to see how high the waters had risen during the night.

From

The sudden capture of the spider in Carson Ellis’ “Du Iz Tak?” When you first read this book, this page is startling and takes you and the characters totally by surprise. (Walker 2016)

The terrifying roar of the lion after having “eaten the whole of the London Symphony Orchestra for breakfast, instruments and all.” Kit Williams "Book Without a Name" (referred to by Williams as "the Bee Book" Knopf 1984)

The unnoticed Elliot from “Little Elliot Big City” by Mike Curato. The sudden shock of loneliness

in a crowded city. You just want to jump in there and rescue him. (Henry Holt & Co 2014)

The mystery uncovered as Bear's secret paper making machine is discovered in Oliver Jeffers “The Great Paper Caper” (Harper Collins 2008)

And lastly the double fold out spread from “Grandpa Green” By Lane Smith where “the garden remembers for him.” (Roaring Brook Press 2011)

What all these examples have for me is a

sense of impeccable timing within the narrative. A moment where the story almost stops, where

the reader might take a breath, absorb and be suspended by, or simply fall into

the illustration. Something wonderfully unique to picture books and akin

to a moment in a film where there is silence, where the camera pans back to

allow the viewer space to consider and ponder what's going on, and perhaps a subtle message for anyone whose finger might be hovering over a red button.

I love these wordless spreads,

not just because as an illustrator they give full reign to the image but because they sit so well within the words adding another visual

moment of texture and depth to the story.

If you have any favourites, let me know.

Garry Parsons is an illustrator. You can see his work here and follow @icandrawdinos

***