|

| Illus by Sarah Gill |

For over ten years I tutored adult education courses on writing children’s picture books. For their first homework I'd get students to type out the text of a picture book where the author and illustrator weren't the same person. This helped demystify picture books and the students would then swap the typed stories and imagine potential illustrations before seeing the 'real' picture books. Although picture book writers don't need to be able to illustrate, it helps to be able to think visually.

During the course I gave students a sheet that listed brief reminders on what we’d covered over the weeks. I thought Picture Book Den readers might like this too. I’ve adapted it and added lots of LINKS to more detailed advice by myself and others at the Den. However, please remember that not every story has to follow all the points raised and I haven’t discussed everything.

Perhaps to begin, just write the story YOU want to write and then think about the points below, otherwise your brain may explode with too much information! Anyway, there are always exceptions and sometimes 'how to' advice only helps when you suspect something doesn't work. Plus always remember to read lots and lots of contemporary picture books and when they're classics ask yourself why they have stood the test of time.

So, in no particular order of importance...

1) Picture books are written to be read out loud so read your story aloud when writing. And if you're feeling brave, listening to somebody else read your text can be illuminating (depressing?!) as we all read differently.

2) As the story is read by an adult to a child, it should appeal to both of them and be able to withstand frequent rereading. Otherwise the adult will be tempted to hide the book or the child will be bored and feed it to a ravenous dog.

3) At its most simple, a story is a problem that needs to be solved. This central problem that drives the plot should be something that matters to a child. So depending on your intended readership, think about what is important to a pre-school child. And assuming your main character is a child (human or animal) then they must solve the problem, not a know-it-all adult.

5) Animals are popular in picture books because they’re cute. Also, they can find themselves in situations that might be dangerous for a child, such as getting lost in the wood or wielding a power saw (the more realistic the story and illustration, the more you need to think about this). Plus an animal is the same whatever part of the world you’re from and therefore more relatable. Having said this, some editors prefer humans.

|

| From Tidy by Emily Gravett (Two Hoots, 2016) It's probably more acceptable and believable for a young bunny to use a pneumatic drill than a realistically drawn human child |

6) Unless you’re self-publishing or are a quality illustrator, you don’t need to be able to illustrate or find an illustrator. The publisher arranges this and you’ll rarely get a choice. If you dislike sugary, cute rainbow-ribboned bears but the experienced publisher insists they’d be perfect, tough luck, the publisher is investing thousands of pounds in the book, not you.

|

| From Come All You Little Persons by John Agard and Jessica Courtney-Tickle (Faber and Faber, 2017) Picture books can be akin to poetry and aren't always straight forward. |

8) Rhyme can be fun if it is of VERY good quality. I avoid it because I don’t have an ear for perfect meter. Plus finding the right rhyme mustn’t be at the expense of the story. I’d often be mean with students and if they wanted to submit a story in rhyme then they had to produce a prose version too. Translating rhyme can be difficult and the French version of The Gruffalo is in prose.

9) Unless you're an incredible illustrator, it's better to concentrate on a good story. There are all sorts of different picture books, but if you don't illustrate it might be easier to stick with more traditional formats, though don't let that stop you (here's a blog post by Pippa Goodhart on how she got a non-story picture book published).

10) Interaction and fun appeal to many children (eg noises, flaps and questions).

|

| From Shhh! by Sally Grindley and Peter Utton A favourite for sharing with brave children - they adore whispering, following the instructions and opening flaps, etc. |

|

| From Firefly Home by Jane Clarke and Britta Teckentrup (Nosy Crow, 2018) There are lots of opportunities for the child to help the firefly find her way home in this beautifully illustrated story. |

11) Repetition and patterning can help provide structure and children enjoy being able to predict parts of the story and join in. A clear structure helps when listening to a story as otherwise the child can be confused and lose focus.

12) Humour is frequently a winner. An agent once told me to have more fun and I remind myself of this when I feel a story is flagging.

|

| From Mother Bruce by Ryan T Higgins (Hyperion, 2015). Full of wry humour aimed at adult and child - it's a little dark and I laugh too. |

13) The Rule of Three can sometimes help a story - it's all explained in the link (this blog post is getting too long!).

14) Word length. A story is as long as it needs to be but 400-500 words is often suggested. Writing short texts is a skill. If you can write a story in 100 words, brilliant! Write you story and then revise and cut, cut and cut. Nobody gets it perfect first time, though don't cut the life out of your story.

15) When writing and revising your story always keep in mind what’s at the heart of the story. This is VITAL and you should be able to describe what your story is about in one or two sentences. Coming up with a good title helps too.

16) Text and illustrations combine to tell story, so allow plenty of opportunity for a variety of images. There can be a visual theme/joke that’s not in words.

|

| From Silly Doggy by Adam Stower (Templar, 2011) The reader can see it's a bear and not a dog, which adds to the delicious amusement, though the text never mentions it's a bear. |

17) If your writing has a strong, distinctive voice/style then that’s brilliant. If you hear a Lauren Child story you know it’s her and vivid characterisation is part of this, which leads to the next point.

18) Characterisation. If your characters aren’t alive in your imagination then they won’t come alive on the page. Think about your main character’s personality and how this comes across in their actions and words. And if you're struggling to bring life to your character, experiment with writing in the first person to get to know your character better.

19) A fun, satisfying twist at the end is a bonus. There's more on endings here.

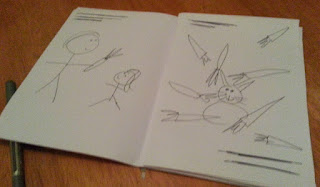

20) Making a simple b/w dummy picture book (stickmen are fine) can help the writer. There’s no need to send this to a publisher unless you’re an illustrator. The traditional 32 pages of a picture book typically allows 24 pages of story (i.e. approx. 12 double-page spreads). If you’re an illustrator you’d also send a publisher just two or three high-quality illustrated colour spreads (not originals and don’t bother doing more as editors always want changes).

|

| A dummy (for your eyes only!) of 8 sheets of A4 folded in half can help a writer visualise how a story progresses. |

21) Think about the overall structure of the picture book. For example, it might be 3/6/3 which equates to three spreads for the beginning, six spreads for the middle and three spreads for the resolution.

22) Your final manuscript can be presented in paragraphs with no divisions into pages, or in the UK you can divide it into 12-15 spreads (safest to keep to 12). I do this because I feel the page turn is part of the story, but opinion varies and don't divide into spreads if submitting to the US.

23) Writers shouldn’t include instructions on illustrations unless something is vital and not understandable from just reading the text. If a lot of illustration notes are essential then send an editor two manuscripts, one with the notes and one without.

24) Remember, even the most renowned of picture book authors write many more picture book texts than are ever published. The ratio varies but I know of one experienced, best-selling, award-winning author who only gets 1:9 published. So don’t despair when your first stories aren’t snapped up –it’s part of being a picture-book author and not pleasant, but that's life. Alternatively, perhaps self publish your book if you feel strongly about one specific story.

At the Picture Book Den there is multitude of great blog posts on writing picture books (naturally, it's a bit of an obsession with us). Using key words and phrases in the 'Search this blog' option on the right of our Home Page will bring up a huge variety. For example, try typing the phrase 'writing picture books'. Happy writing!

Paeony Lewis www.paeonylewis.com

17 comments:

This post pulls together a wealth of valuable information Paeony, thank you. Very inspiring for those of us who have story ideas but struggle to get them to paper without a meltdown.

Wow what a lot of great tips! Thank you

So much to learn, and loads of great books to read for inspiration. Thank you so much :)

Thanks, Garry! And I'm jealous of your illustration skills :-)

Thanks, not that you need any, Lucy!

Delighted it's useful, Martin. Thanks and good luck with your reading and writing!

Thank you so much, Paeony! This is very timely for me as I'm close to submitting my first picture book to some publishers. Such great advice - thank you!

Just fantastic, Paeony. I love getting all of these reminders to keep me on the right path.

Many thanks, Kit, and good luck!

Thanks a lot, David. I'll admit that even though I know stuff I sometimes need reminders too - I helped myself!

Thanks, Paeony. What a useful post. And I love your examples. I'm just about to order three of them! Really interesting examples.

Great. Thanks.

Many thanks, though you know it already, Clare!! And I'm glad you like the examples - I tried to pick books from my shelves that weren't necessarily known by everyone but now I'm worried you won't enjoy them!

:-)

Great advice. Thank you!

Good luck with your writing!

Thanks for sharing this amazing informative post with us i found this helpful for fiction book editor specializing in children's and young adult literature provides Childrens books & Young adult fiction books. Order Online! Kids book editor

Post a Comment